3.1 Introduction to UK housing stock

Free PreviewMain contributors to Module 3

Andy Simmonds, Unison/Sheffield Hallam University (see note below)

The key objective of Module 3 is:

- to provide a firm foundation of understanding for developing robust and appropriate retrofit strategies for buildings of different constructions, materials and ages

by:

- starting with a background in the most common construction styles in the UK

- introducing some of the variations and less common examples of construction in the UK

- illustrating how the style or condition of the existing building can affect retrofit strategy

Module 3 consists of the following lessons:

Lesson 3.1 – Introduction to UK construction methods, materials and history

Lesson 3.2 – Traditional construction – methods and materials

Lesson 3.3 – Non-traditional construction – methods and materials

Lesson 3.4 – Retrofitted examples of traditional and non-traditional buildings

Lesson 3.5 – Walls – regional and local variation

Lesson 3.6 – Floors – regional and local variation

Lesson 3.7 – Devising retrofit strategy with existing defects in mind

Lesson 3.8 – Homework

We recognise that some undertaking this course will know much of the content of Module 3 already (e.g.e architects or builders). However, others may have not covered this background information previously (e.g. home owners who are driving their own retrofits, or energy consultants who so far have little experience of building fabric).

Note regarding source materials in Lessons 1, 2 and 3

In this module we take a look at some of the variety of UK building types – predominantly older buildings.

Much of this material was originally part of a UNISON Open College distance-learning programme.

The UNISON material was originally prepared for Housing Managers working for Housing Associations and is generally written from this perspective. In the CLR use of this material, the term ‘Housing Manager’ has generally been changed to ‘retrofitter’ to reflect the CLR focus. Original source, accessed 22.12.15 (suggested reading 1) http://teaching.shu.ac.uk/ds/housing/hnc/year_1/course_material/housing_construction_and_property_management/HCPM101_00.pdf

It is now jointly owned by UNISON/Sheffield Hallam University who have very kindly allowed the AECB to make extensive use of this material.

The AECB takes responsibility for any errors and omissions in its use as part of the CLR course.

By the end of this lesson you will have learned about:

- The relevance of house construction and history

- The evolution of construction methods and materials

- House construction over the last 100 years

Recommended reading

This 23 page report from the BRE Trust covers the history of housing surveys, the main UK housing survey models and describes the UK’s housing stock. The Housing Stock of The United Kingdom, published by the BRE Trust. [added 11.04.21]

Lesson 1 – Introduction

Here, we will look at dwelling classification & other ways of categorising buildings or parts of buildings.

We will cover the main methods and materials used in house construction pre-1960. The relevance of some of these characteristics when considering a retrofit will be highlighted.

Although this section currently stops at the end of the 1960s, the intention is to extend it in the future. Currently, the majority of homes undergoing low energy retrofit (but by no means all) were built pre 1960.

1. The Relevance of House Construction and History

Understanding the existing fabric is central to understanding how it will respond to energy efficiency measures, such as increasing airtightness and insulation.

It is critical that retrofitters are able to distinguish between building maintenance / repair problems and problems caused by poor retrofitting…

For example:

Damp might be caused by:

- lack of a damp proof course,

- a compromised damp proof course,

- poor pointing,

- a leaking gutter,

- but it might also be caused by a thermal bridge…

e.g. where increasing insulation in the loft creates cold spots at the eaves – which then lead to mould growth on the ceiling inside.

It is important that the maintenance and repair issues are solved before or as part of the retrofitting.

One of the biggest challenges for retrofitters is to be knowledgeable enough to distinguish between these issues. That is to have enough knowledge of building detailing and materials to analyse problems effectively.

And then there is the big issue of understanding how the retrofitting strategy will impact on the existing material. Energy and moisture issues are central to this question and dealt with in Modules 4 and 5 respectively.

With an understanding of the building fabric make up, we can assess where adding insulation and airtightness will compromise the existing building’s moisture management system. In general, buildings have been designed with an understanding of the capacity of the materials and designed to cope as they are. To change that design by altering the insulation and airtightness requires a sophisticated understanding of moisture and energy management.

Activity:

Thinking about your own home or imagine that you are the owner of a project you are working on… Make a list of repair or maintenance tasks that:

- you have already had to do

- you have checked but don’t need doing yet

- you have not checked but probably should check

- you expect to do in the next 5 years

- you expect to do if you stay in the house in the long term

2. Evolution of Construction Methods and Materials

Building construction has changed greatly over the last 150 years due to a wide range of influences. These are as diverse as metrification, the urgent need for additional housing after two world wars, changes in desired living conditions, building standards and energy standards.

In the context of the CLR course, a major influence is work more recently carried out on the ‘building performance gap’. The AECB network and the Passivhaus community are doing this by focusing on rigorous low energy design, construction and certification (e.g. AECB Building Standard and the Passivhaus Standard).

The common factor with AECB and Passivhaus Standards is the underlying methodology and conventions and, specifically, the use of the building modelling software – the Passivhaus Planning Package (PHPP). There is also a common focus on design and construction Quality Assurance based on evidence-based certification.

The AECB has a self-certification approach for its Building Standard whilst the Passivhaus Institute offers a formal network of accredited UK certifiers for the various Passivhaus Standards – see the Passivhaus Trust for details of UK certifiers.

Legislative changes have been driven by the connection between poor housing and health, leading to a number of Acts of Parliament from the Victorian era onwards. These established basic requirements for sound housing conditions, including:

- adequate sanitation,

- adequate water supply,

- freedom from damp,

- adequate natural light,

- adequate ventilation.

Some of these criteria are covered by the Building Regulations introduced in 1965 and since amended. The primary purpose of the Building Regulations is to establish minimum standards for the health and safety of occupants. They do not define quality or levels of workmanship.

Besides the statutory obligations, a number of sources of authoritative advice seek to establish good building practice.

- Perhaps the most significant is the British Standards Institution (BSI), which regularly publishes detailed guidance on a variety of technical matters. These include:

• British Standards which cover such areas as the quality and dimensions of materials;

• Codes of Practice which cover wider issues such as building design and construction method. - Other authoritative advice is published by the British Board of Agrement, which appraises new products and techniques, and by the Building Research Establishment, which provides a number of invaluable reports and digests on all aspects of construction.

- Trade bodies such as the Timber Research and Development Association (TRADA) and the manufacturers themselves also produce excellent guides on specific products. Finally, most volume house-builders are members of the National House-Building Council, which sets out minimum standards of construction and produces regular bulletins relating to building defects.

More recent sources of advice include the Energy Saving Trust (EST) Best Practice Programme, AECB CarbonLite Programme and the Passivhaus Institute and the UK’s Passivhaus Trust.

3. House Construction over the Last 100 Years

Now we look at the different ways in which houses have been constructed since the latter part of the last century and suggest a classification of house construction since 1900.

Categories

Housing stock can generally be categorised and identified as Old Traditional, Prefabricated, Traditional, Rationalised Traditional, or Industrialised and it may be that if present experimental work is successful, new categories will be established in the future. In the following notes, an attempt has been made to date the various categories, but these are approximate, as each category was slowly superseded by another.

Typical key features of dwellings in each category are described below:

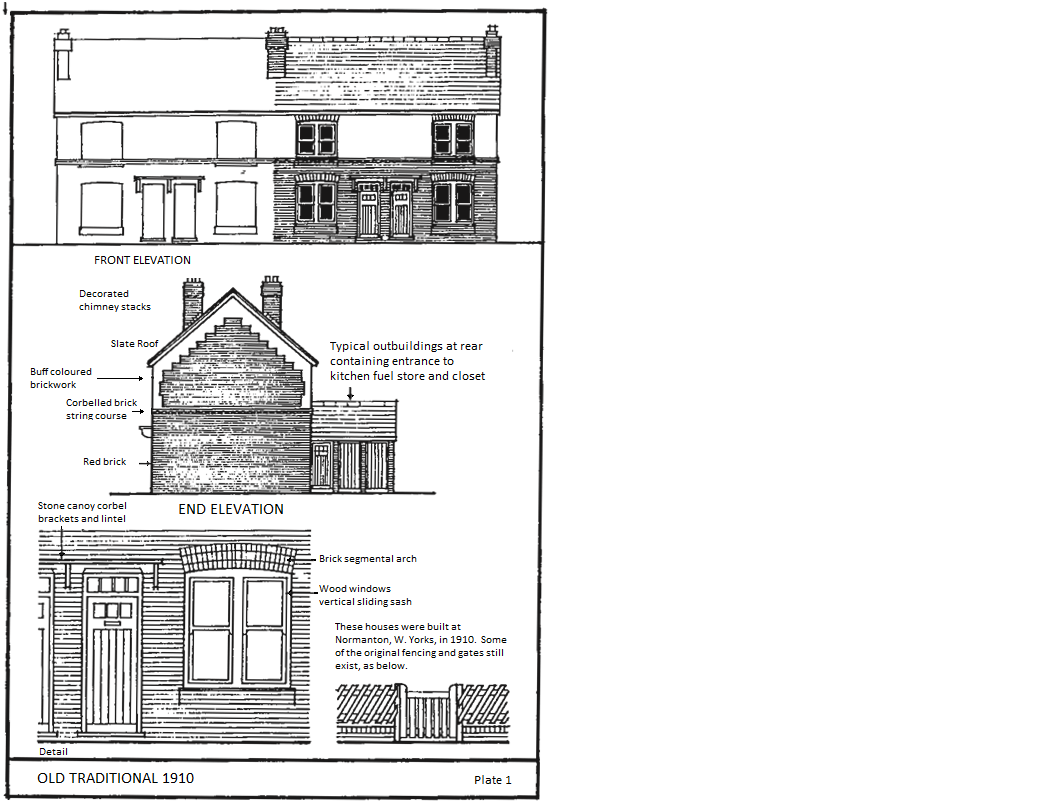

Old Traditional 1900-1930

These had solid external walls of locally produced bricks, on brick foundations, no damp courses, segmented or flat arches to door and window openings, with much use of brick string courses and cills and large areas of cement rendering etc.

Roofs were pitched, of timber, many with no underfelt, and covered with slates or clay tiles, with mainly cast iron gutters and fall pipes.

Ground floors were often solid to kitchen and storage areas, and of suspended timber construction to other rooms and upper floors.

Kitchen and store walls were frequently unplastered.

Ceilings were lath and plaster.

Windows were generally timber, vertical-sliding sash.

External and internal doors were either panelled or boarded.

Kitchens had very few cupboards, if any, and the free-standing sink often had no drainer. The food storage consisted of a cold slab and shelving in a separate larder.

Most rooms had open fireplaces and occasionally, an open cauldron-shaped water boiler with lid, in the kitchen.

Internal plumbing was in lead. Some houses built in 1910 are illustrated in Plate 1 (below).

Note regarding images: All the images in this lesson are for illustration only (these are the best resolution that we have available). You do not need to read or remember the features named in the annotated diagrams for the purposes of this course.

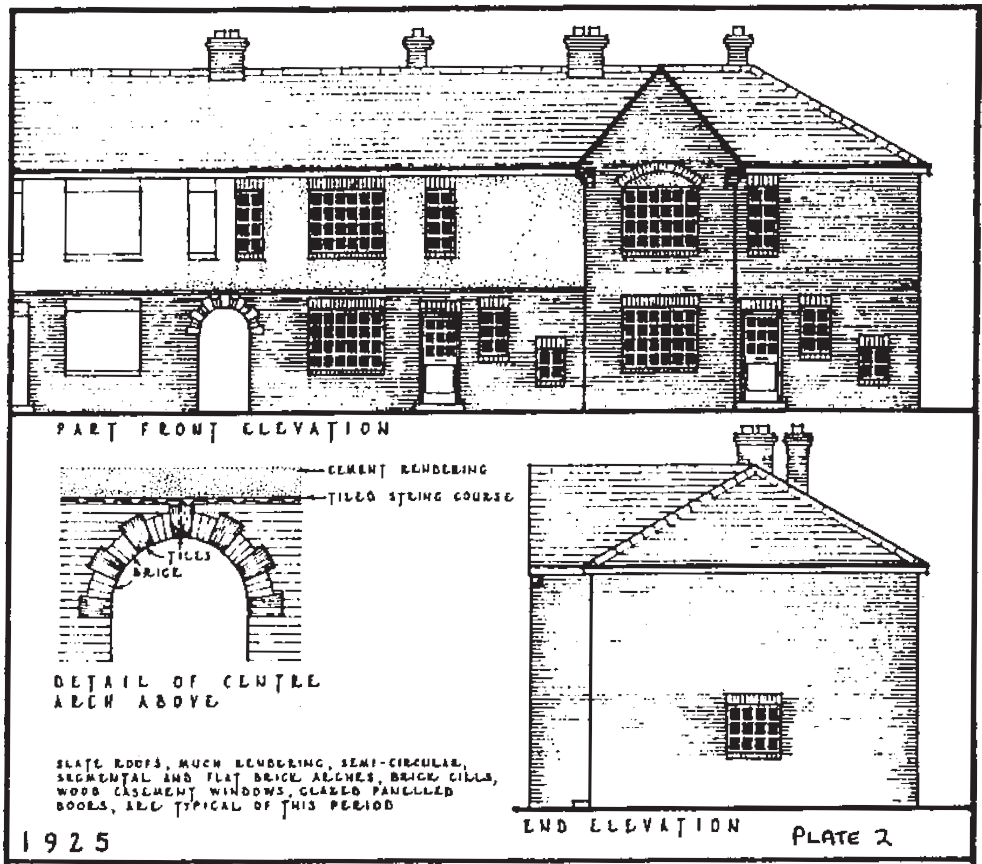

Damp courses were gradually introduced in the 1920s and an example from 1925 is shown in Plate 2.

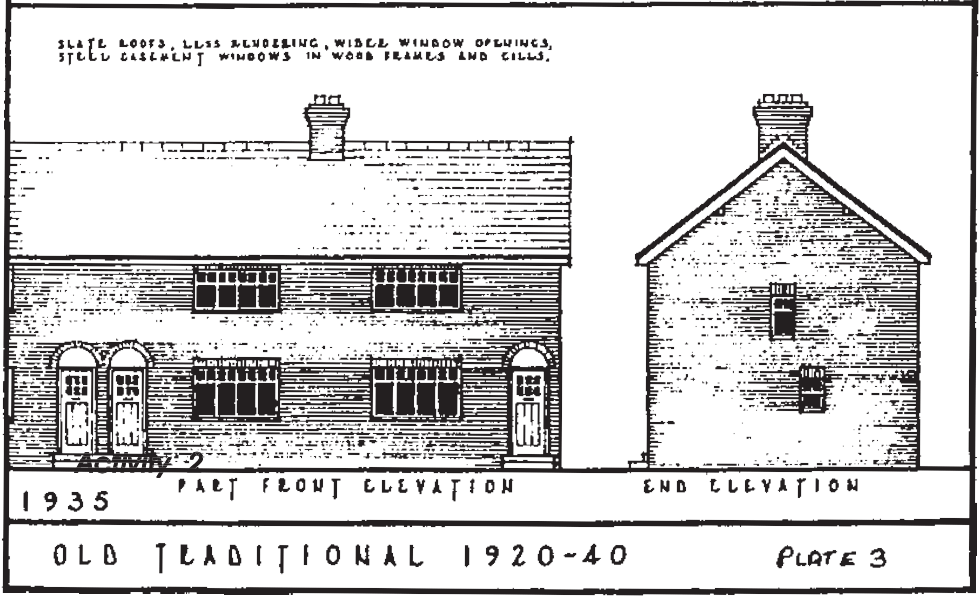

Old Traditional 1930-1940

Cavity external walls (still of local bricks) were gradually introduced around the 1930s on concrete strip foundations and damp courses were in common use.

The external appearance was slightly less ornate and timber or steel casement windows were introduced.

Roofs now had underfelt, but were still uninsulated.

Cast iron or wooden gutters were provided.

There was some improvement in the provision of kitchen fittings, and all walls were now plastered, but many bathrooms were still positioned on the ground floor, usually directly off the kitchen.

Open fires were still provided to the main rooms.

Lead internal plumbing was gradually replaced by iron or galvanised steel. An example is shown in Plate 3.

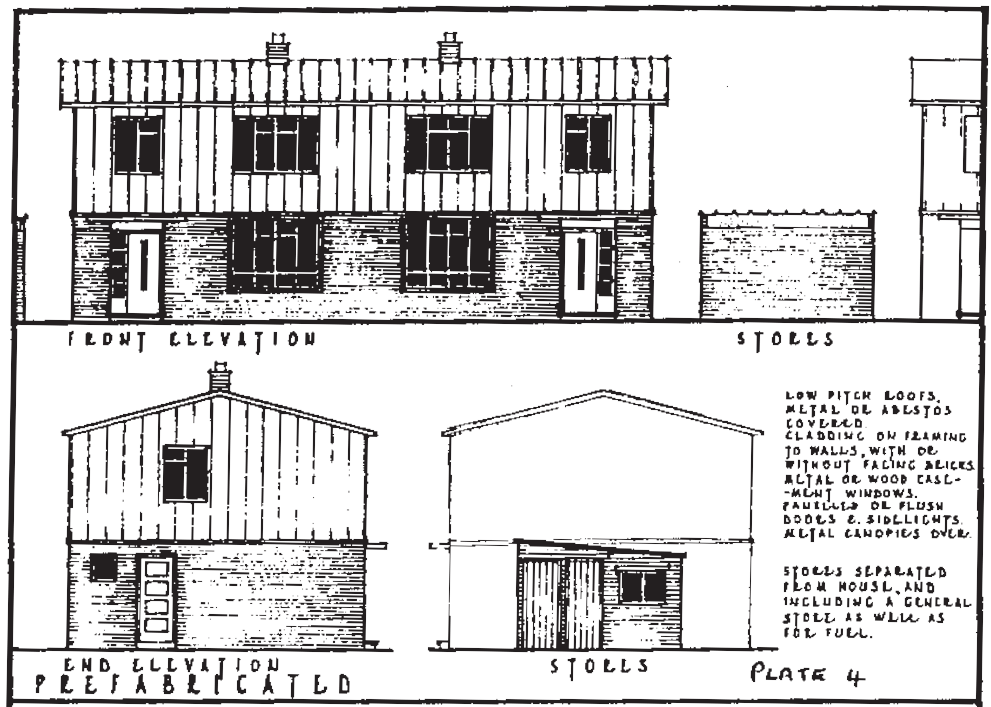

Prefabricated 1945-1950

After the second world war, there was an urgent need to replace the thousands of houses destroyed, particularly in the cities, and many more were required to provide first homes for the vast numbers of service personnel returning to civilian life.

Practical considerations controlled the rate of demobilisation and there was insufficient time to provide either the materials or suitable labour, to meet the requirements by traditional building methods.

However, there were many factories which had been geared to the war effort, which were suitable for redirection towards the mass production of both new materials and those not previously in common use, e.g. fibre boards and aluminium and these were utilised.

As far as possible the resultant designs were prefabricated in the factories, using non-traditional materials, in order to reduce the time and skilled labour required on site. They were of frame construction, (generally with trussed roofs of very low pitch), and clad with a variety of materials, including asbestos, steel, aluminium, and concrete, although some were provided with an external skin of traditional brickwork.

Metal casement windows of widely different design were in common use and internally maximum use was made of fibre and plasterboards, for wall, ceiling and partition linings. The provision of kitchen facilities was greatly improved with the introduction of mass-produced cupboard units (some of metal construction) and the inclusion of free-standing cookers and refrigerators. Heating was often provided by an open fire in the living room, and closed stove in the kitchen, with some attempt to provide background heat elsewhere.

There was a greater provision of electric power points than previously and whilst subsequent improvements in standards evoked criticism of the performance of some of these dwellings, the better ones are still regarded with some affection by both past and present tenants. See Plate 4.

A minority of the prefab designs were only intended to have a short or restricted life span and yet gave many years satisfactory service. Of these designs, one in particular was so successful that many tenants were reluctant to transfer to more modern houses, even after being informed that demolition was essential, due to structural deterioration.

Traditional 1945-1960

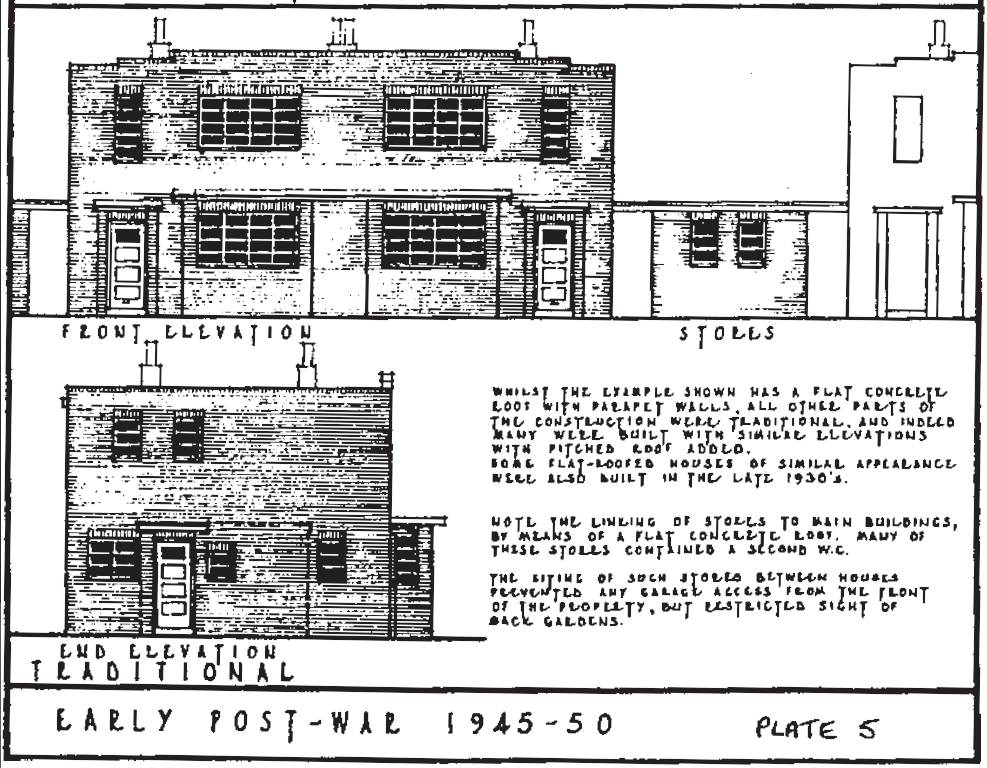

There had been some traditional building during the prefab era, and this was gradually increased as more skilled labour and materials became available. Of necessity, most Authorities simply resumed building to the same designs as had been used just prior to the outbreak of war and whilst pitch roofs had always been predominant, some flat-roofed dwellings had been introduced and these also continued. Flat roofs were of timber or concrete, felt or asphalt-covered, with parapet walls to the edges, and an example is shown in Plate 5.

Apart from the roof, the rest of the construction and fittings was identical to that of the pitched roof dwellings built in this period but many maintenance problems were to occur, simply because of the flat roof construction.

Initial improvements to the road network, greater availability and use of motor transport, permitted less reliance on the use of local materials and made available a wider selection of facing bricks of many colours and textures.

Concrete roofing tiles of different colours and profiles were introduced.

Coke breeze building blocks of various thicknesses were readily available for internal walls, partitions and inner leaves of cavity walls.

Pitched roofs returned to a more traditional (steeper) pitch than the prefab type.

There was much use of asbestos gutters and pipes.

Windows were wood or metal casements, doors flush.

Some form of background heating was very occasionally included.

Copper pipework and wastes were used and also either separate cookers or combined heating- cooking appliances.

Solid floors were either thermoplastic-tiled or asphalt-covered.

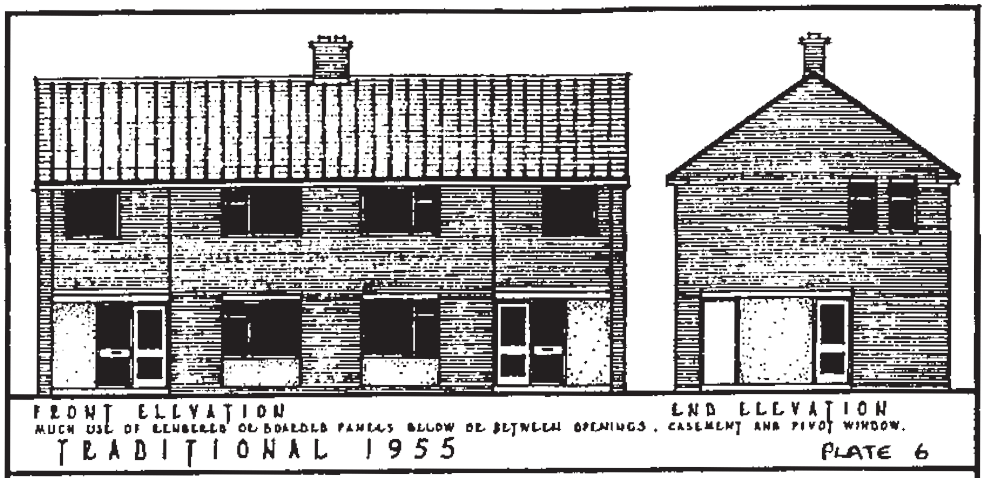

Towards the end of the 1950s, plastic gutters and pipes were introduced, together with pivot windows, and more use was made of glass panelled external doors. Separate cookers and heating appliances had now superseded the combination range but provision of background heating was still limited and individual electric wall fires often used to supplement the main heat source. More variety was introduced into the external appearance by the use of small panels of cement rendering or timber boarding and reinforced concrete boot lintels (sometimes with projecting concrete window surrounds) were introduced. See Plate 6.

Rationalised Traditional late 1950s-early 1960’s

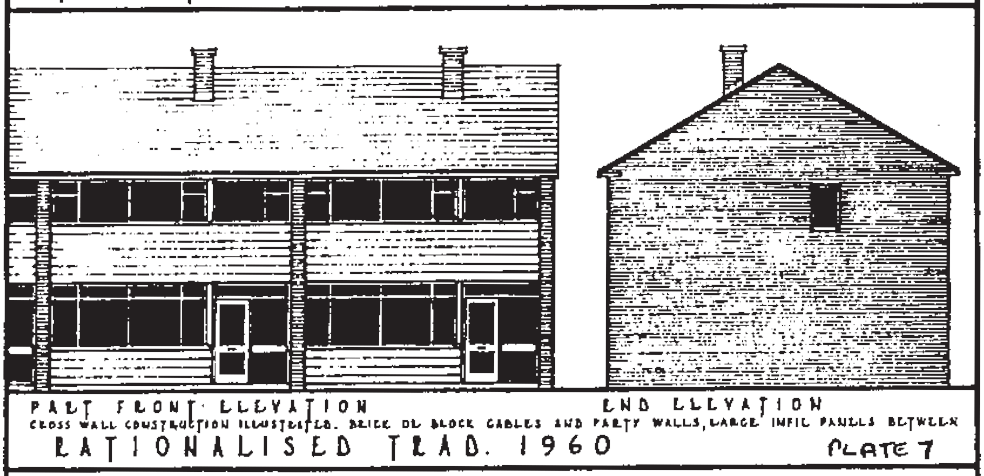

In the late ‘50s and early ‘60s, fresh efforts were made to improve efficiency and speed in the traditional building process, by the combination of modular-controlled, factory-produced components, and traditional practices on site, i.e. by rationalising the traditional approach. Probably the best known of these is the cross wall construction, involving brick or block gables and separating or ‘party’ walls, set out to receive infill panels to front and rear elevations. These panels were produced off-site and often only required the addition of window glass and external door hanging after installation. Such panels were generally timber framed, covered with a variety of materials, e.g. boarded or plywood/asbestos panelled. See Plate 7.

By the early ‘60s some Authorities were already introducing some form of central heating, if only to the ground floor rooms. However, by the late ‘60s all authorities were doing so following the introduction of mandatory heating and space standards, as recommended earlier in the Parker Morris Report.

Industrialised

The rate of house building had not kept pace with housing needs. Accelerating slum clearance programmes and the anticipated post- war population boom, were creating a huge housing deficit and drastic measures were required.

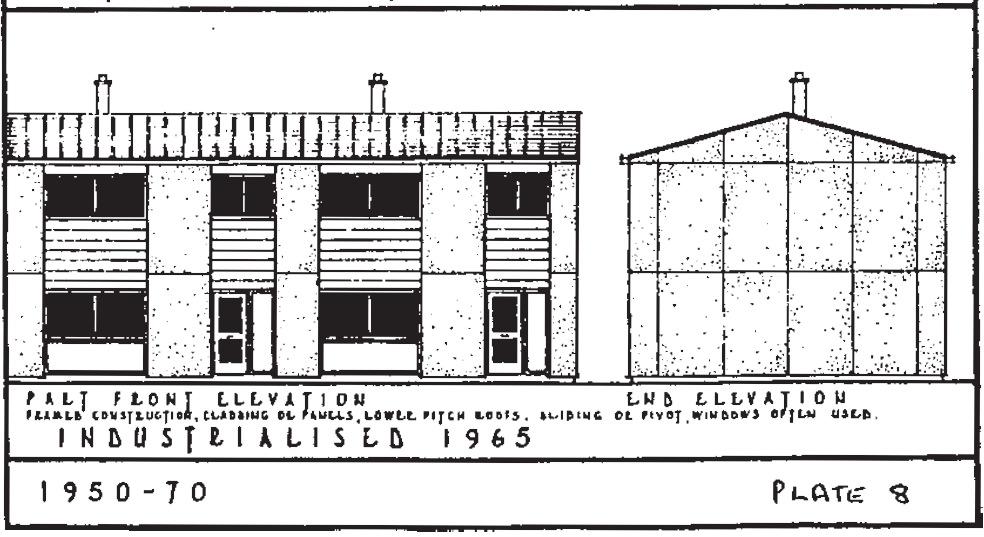

A vast number of modular building systems were developed using new techniques, materials and maximum use of factory produced and assembled components, which could be so arranged on site as to provide some variation in the external appearance of the dwellings, or internally, to permit the use of a standardised bathroom layout within houses of varying plan arrangements. They generally consisted of a structural frame of timber, steel or concrete, usually with infill panels, or sometimes with an outer skin of brickwork to create a more traditional appearance. In many cases, concrete was the basic material for both the structure and external shell of the dwelling with the emphasis on prefabrication off-site, or cast in-situ using the ‘no fines’ principle. Most building systems were also designed to allow greater flexibility in the choice of heating installation and waste disposal was by the single stack system. See Plate 8.

Such provisions should have improved the living conditions of the occupants.

Unfortunately, some building systems relied too heavily on the use of joint sealants, whilst others may have been too enthusiastic in their acceptance of some continental building techniques, which were designed for different climatic conditions to those prevailing in this country.

At least one system was designed to such critical structural limits, either through ignorance or economic pressure, that it became unstable in extreme weather conditions. It would have required a degree of quality control during fabrication and construction that was virtually impossible to achieve, given all the vagaries of our weather and the building industry.

At the peak of the industrialised period there were over two hundred systems on offer, some of which were promoted by companies who had previously only supplied an individual building component. They simply attempted to provide a complete system around it, with insufficient experience or knowledge of the overall problems of housing design and construction.

It was, therefore, obvious that many of the systems could not possibly survive the intense competition, and some Local Authorities took this into account, together with the implications for future maintenance when making their selections. Furthermore, industrialised systems were seen as a threat by traditional building contractors, many of whom reacted by offering their own ‘design and build package deals’ as an alternative.

Of the failures during the Industrialised Period, some were predictable and should have been avoided. Others were not so obvious, and whilst, with hindsight, some criticism of the designers, builders and Local Authorities is warranted, they were subject to the policies, pressures and financial or design constraints of successive central governments and their agencies. The financial and social legacy of such policies has already compelled some Local Authorities to demolish various industrialised dwellings after twenty years, which were intended to last for a minimum of sixty years – rather than attempt to maintain or improve them to a satisfactory habitable standard.

Whilst routine maintenance and repair of minor defects occurring in the successful systems is often similar to that required for more traditional housing, detailed knowledge of the particular building system is essential when more serious faults are being examined. This also applies to prefab. housing and is beyond the scope of this course.

As an example of fitting commonly termed house types into these categories, some house types in Leeds were identified as:

- Victorian terraced houses

- Edwardian villas

- Back to back street houses

- Interwar semi-detached houses

- Unity (prefabricated) houses

- The Macmillan People’s House

- Deck access flats

- High rise block

- Modern estate house

- Timber framed house

The categorisation exercise above gave the following result:

Old traditional

- Victorian terraced houses

- Edwardian villas

- Back to back street houses

- Interwar semi-detached houses

Prefabricated

- Unity (prefabricated) houses

Traditional

- The Macmillan People’s House

- Modern estate house

Industrialised

- Deck access flats

- High rise block

Rationalised traditional

- Timber framed house

Whilst there might be some argument about some of these classifications, (for example is modern timber framed really a rationalised traditional form of construction?), such exercises are useful in that they requires you to think in more detail about the different ways in which houses have been built over the last century.

Focusing on the local specifics of areas and regions of the UK will help avoid problematic ‘one size fits all’ approaches to national retrofit activity.

Suggested reading:

The following NHBC guide also documents the key changes in housing through time, up to and including the present.

https://www.nhbcfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/NF62-Homes-through-the-decades.pdf

Summary

This lesson has covered:

- A brief history of house construction and materials in the UK

- A summary of legislation changes

- Sources of authoritative construction advice